-

European Stages

The year 2012 marked the centennial of August Strindberg’s death. His persona and artistry held center stage in the many productions commemorating the poetics of one of the founding fathers of European modernism. For the Swedish Cullberg Ballet this was an opportunity to pay tribute to one of Sweden’s major national culture figures and to re-examine the legacy and the memory of Strindberg.

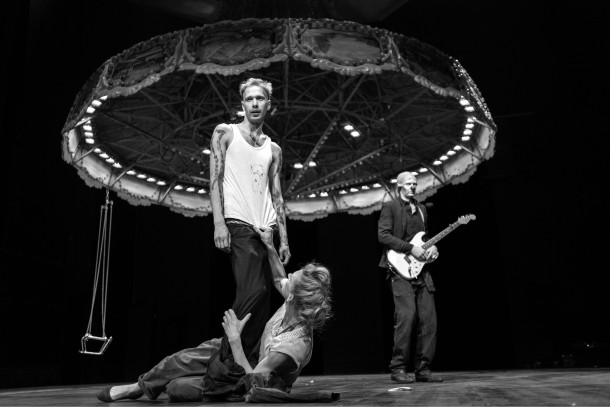

The Strindberg Project, a dance performance by the Cullberg Ballet, premiered in March 2012 in Stockholm (the Strindberg project is co-produced with Festspielhaus st poelten, Austria). This performance does not present August Strindberg’s biography, nor is it an adaptation of any of his dramatic or literary works. Instead, it seeks to investigate the cultural and artistic memory of Strindberg as an iconic figure.

A Swedish icon in its own merit, the Cullberg Ballet, a part of Riksteatern, Sweden’s National Touring Theatre, unsurprisingly rose up to the challenge and readdressed the works of Sweden’s literary icon. This is not the first time the Cullberg Ballet stages a choreographic interpretation of Strindberg’s works. In 1950, the centennial of August Strindberg’s birth, Brigit Cullberg, founder of the dance company, adapted his play Miss Julie (1888) as a ballet and created a performance that won her company world acclaim as it became one of the most staged and popular ballets of modern times.

More than half a century later, the Cullberg ballet produces The Strindberg Project—a performance that deals with the relations between the author’s artistry and his interpreters; it questions the presence of iconic cultural figures in our lives and seeks to understand their part in staging our identity. This performance thus encapsulates a multi-layered cultural dialogue between the dance company and an emblematic figure in Swedish culture, presenting contemporary perceptions of Strindberg’s poetics and examining the relevance of his presence as a cultural symbol. Accordingly, in this review I wish to examine development of understanding and thought about Strindberg’s authorial voice.

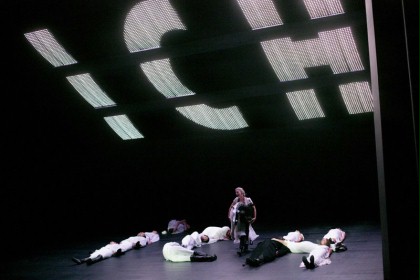

This project consists of two parts: the first, titled August did not have what is commonly considered good taste as far as furniture is considered, was created by dancer and choreographer Tillman O’Donnell; the second part of the performance, created by theatre director Melanie Mederlind, is titled Translations. The two parts differ in their themes, scenography and choreographic language. Whereas the first part of the show presents a white cubic stage on which Strindberg’s mental illness is presented in regard to his poetics, the second part of the production shows a dark space focusing on Strindberg’s occupation with the Chinese language during his later years. However, despite these differences both parts of the project attempt to shed light upon the gap between the poetics and persona of Strindberg and its contemporary understanding by redrawing the boundaries on stage between the vocal and the visual, between what is heard and what is seen.

The performance showcases a performative approach that perceives the stage not only as a visual and physical place, but also as an acoustic one. The danced sequences in this performance are combined with scenic miniatures that include acted episodes as well as group sequences in which the dancers recite texts and perform vocal acts: they speak, sing, shout, scream, and bark. The dominant presence of vocal acts in a highly visual performance offers a discursive investigation of the tension between the dancers’ bodies and the natures of their vocal acts.

Vocal acts in contemporary dance performances are often regarded as secondary texts in the construction of the mise en scène. In contrast to this approach, this review considers the voice a primary element in the staging of the dancers’ bodies and in the communication of the performative experience. I am referring here to the notion of voice as a generative principle that operates in two registers: in the first, the voice is understood as a metaphor signifying Strindberg’s authorial identity. In this register imprints and echoes that characterize rhetorical features of Strindberg’s poetic style are traced and revealed.

In this performance Strindberg’s authorial voice is depicted in representations of characteristics from his dramatic techniques. These include the spatial perception and the cinematographic effects interlacing the different scenes in the performance. The second register refers to the materiality of the vocal utterance as manifested in this performance. The after-effects of Strindberg’s dramatic techniques and public persona regain their presence through the vocal configurations performed by the dancers. These include fragments from his writings and abstract vocal acts that stage aural images and metaphors from his plays.

During the first part of the performance, three small photographed portraits of Strindberg are present on the stage. The performance space thus prompts a stage in the spirit of Strindberg who haunts it as a visual image and as an authorial presence. Moreover, this space materializes an abstract interpretation to some key elements from Strindberg’s fictional worlds. Freddie Rokem has noted that the stenographic metaphor of a claustrophobic space was frequently used by Strindberg to express a universal determinist human condition (2004:34). The same spatial logic is applied to the stage: in the first part the stage is designed as a wide closed room with few articles of furniture, where six dancers are imprisoned. In the second part of the performance, the black cubic stage is marked by white masking-tape outlining the borders of the imaginative habitual space of the dancers.

As in many of Strindberg’s fictional worlds, the actual stage action is dynamic and multifocal. The first part of the performance unfolds in a fragmented flow of scenes, scenarios and dance sequences montaged together by associative logic. This effect is reached mostly through the stage-lighting design. Three fluorescent lights hang above, illuminating and darkening the space in interplays, thus producing the impression of edited moving-pictures, creating a cinematic effect that echoes Strindberg’s preoccupation with the art of photography. Sometimes the scenes cross-fade into each other; at other moments they shift abruptly from light to darkness. The stage lights thus manipulate the audience’s perception as the viewers’ angle of vision jumps from one spot to another. Strindberg’s interest and experiments with the aesthetical and rhetorical features of photography is furthermore cited in the second part of the performance, by combining video close-ups from the staged action.

In both parts of the performance the dancers present exaggerated notions of Strindberg’s public identity, ridiculing the clichés that comprised contemporary understandings of Strindberg: misogynous, mad, and inspired. At these moments one cannot avoid noticing a sense of self-reflexive irony regarding the applauding of a symbol, seasoned with irony at the habit of butting the icon.

August Strindberg’s artistic voice is thus the substance of this performance, carried out and heard through a fabricated dialogue with the sensual materiality of the dancers’ physical and vocal actions. Features from Strindberg’s poetics are mediated by the performers, undertaking the action of utterance, and simulating the author’s artistic voice. The dancers’ bodies are transformed into an artistic sign by the syntax of their choreography: throughout the first part of the performance the dancers present repetitive movement motifs of fractured, stand-still and fast-forwarded dance sequences. These physical configurations resemble the moves of animated figures, or marionettes movements, and create the image of dancers that have lost control of their body.

Hence, the choreographed syntax presents the dancer as a vehicle to channel the voice of the author—be it the choreographer or August Strindberg. Positioning the dancers’ corporeality as an apparatus to stage Strindberg’s voice indicates a fundamental distance between the narrating agent—the performers—and the narrated object—August Strindberg. Melanie Mederlind acknowledges the discrepancy between the theme of the performance and its enactment, as she explains in the performance website: “I want to take in the different linguistic backgrounds of the dancers and create an ensemble piece out of language, associations and images.”

The gap between the author’s voice and the body of the dancer producing it is presented by staging the non-linear relations between the heard voices and the performers’ bodies. Three central vocal practices formulate these relations: the first is the barking dancer; the second is the female voice-over and the third is the conflict presented between the source text and its translator. These strategies stage a voice that is detached from its source and attached to a separate, perhaps disembodied existence.

The first vocal practice refers to the materiality of the voice. The vocal act of barking is repeated in various phases of the first part of the show, accompanied by the imitation of doglike behavior. Although Strindberg was well known for his fear of dogs, uttered barking presents a common motif in his drama: Strindberg’s fictional characters are often driven by their untamed urge to a fatal condition that reveals their animal-like nature. An obvious example of this can be found in the scene from Miss Julie where Julie’s purebred dog who had been consorting with the gatekeeper’s mutt, is presented as an analogy to Julie’s condition in the kitchen: the pet dog is in estrus and Kristin tells Jean that it is Julie’s “time of the month” that is making her behave strangely.In a similar fashion, the dancers in O’Donnell’s performance are captured in recurring movements and vocal patterns that echo the repetitive behavioral pattern and the expected and uncontrollable archetypical schemes often presented by Strindberg characters. From this point of view, the barking serves as a vocal act that animates a universal primal mental condition of characters enslaved to their behavioral configurations and inescapable drives.

At one point during this scene, the delicate balance between the different movement patterns of the dancers on stage is violated and a storming and aggressive attack of the dog troupe begins. The moment of attack presents an abstraction of a familiar moment in Strindberg’s drama, in which the characters rip off their domesticated and educated masks and expose a beast-like aggression in their carnal lust for prey. “To eat or be eaten- that is the question”—Strindberg dictated these words to the Captain in his play The Father (1887). This statement is further exemplified in the performance by presenting the vocal lateralization of the metaphor. In the second part of the performance, the carnal metaphor is translated in the sublimation of the actual act of eating, as the dancers peel and bite oranges.

The moment of the savage attack also presents the formation of a community comprised of resonating bodies sharing the Darwinian survival struggle. Noises from the aggressive assault continue to flood the acoustic space long after the stage is darkened. During these moments the viewers’ field of vision revoked, and their stimulated imagination and fantasies replace the necessary visual anchor. In these moments the performers’ voices serve as voice-overs and create an alternative mental image of the assault. The audience experiences the actual process of acknowledging bestial human nature as it hosts the voices of the brutal attack in its mind.

The second mode in which the notion of voice operates in this performance is the disembodied female voice-over. During the first part of the performance the entire cast wears fake beards and moustaches, imitating Strindberg’s. These visual attributes signify that the performers’ corporeality is inscribed and authored by Strindberg’s own male persona, both textual and corporal. However, despite the male dominance of the visual score, the configuration of the disembodied narrator’s voice as female suggests the supremacy of the feminine in the acoustic space. In this perspective, the female voice-over repositions the familiar Strindberg theme of the gender-based battle as a conflict between the visual stage and the acoustic space.

Who then wins this battle? Throughout different moments of the first part of the performance, a female voice-over recites a text describing Strindberg’s mental and social peculiarity. This text is delivered in perfect diction with a distinct American accent, creating an acoustic image of an act of patronage. The female voice-over thus disrupts the male dominance of the stage and alters the perceptual hierarchy of sound and image. By using the reference to Strindberg’s iconic look, the battle between the sexes shifts to one of dominance between the author’s voice and its enactment. Understood from this perspective, the female voice-over emphasizes the split between the authorial voice and the actual place of its production.

The third, and final, mode of the voice focuses upon the tonality of Strindberg’s language through the concept of translation. The aural and acoustic aspects of Strindberg’s drama are hardly a present aspect of his staging, since most of the performances of Strindberg’s works are nearly always translated. The second part of the performance illustrates this idea, as Egil Törnqvist has pointed out, Strindberg’s plays are dependent on their translation due to the simple fact that few non-Scandinavians have any knowledge of Swedish (2000:53). The voice in this performance is present through the different sounds and accents of the language games performed by the dancers.

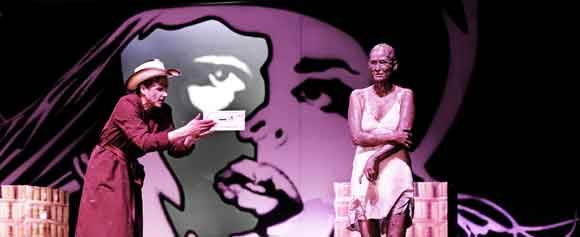

The associative image flow of Strindberg is performed by a multilingual translation combining video projection, Cha-cha-cha dances, and echoes of fragmented writings by Strindberg. In this part of the performance the act of translation is played out through the reconstruction of Strindberg’s poetics in a new form. His authorial voice collides with a shifting flow of imagination and conception of China, merging with the dancers’ various national and personal identities.

To conclude: the vocal practices I have presented outline the acoustic dimension of the performance as one that emphasizes the liberation of the voice from its source. However, while the voice detaches Strindberg, it symbolically reattaches itself to the corpus of August Strindberg—it animates his voice and translates it into a contemporary artistic language. August Strindberg died a century ago. His artistic pulse, however, continues to beat as it reverberates in the bodies of his adaptors, translators, and interpreters.

Ruthie Abeliovich is a Post-Doctoral fellow at the ICORE Center for the Study of Cultures of Place in Jewish Modernity at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem. She is an adjunct lecturer in the Theatre Studies Department at

the Hebrew University, at the Interdisciplinary Program in the Arts (Graduate Program), and at the Western Galilee College. She recently completed her PhD titled: “Voice, Identity, Presence: The Rhetorics of Ventriloquism in Contemporary Women’s Voice Art,” in the Department of Theatre Arts at Tel Aviv University.” Her main academic interests are feminist performance-art, and theories of sound, voice and embodiment. -

European Stages

New Policy at the María Guerrero

In past issues of WES, I have overtly lamented the relative absence of living Spanish playwrights from Madrid’s public stages: the National Drama Center (CDN) and the municipal Teatro Español [WES 12.1, Winter 2000; 12.3, Fall 2000]. My failing to place the problem center stage later did not mean it had disappeared. In 2012-13, however, with playwright/director Ernesto Caballero (born 1957); [WES 18.3, Fall 2008] at the CDN helm, the national stage is actively promoting the nation’s dramatists. Prior to assuming this position in January 2012, Caballero announced that Valle-Inclán (1866-1936) and García Lorca (1898-1936) would be pillars of his programming; this year he has turned to contemporary authors. The season began with Los conserjes de San Felipe (Cádiz 1812), a history play by José Luis Alonso de Santos (born 1942). Because the María Guerrero was still under renovation, that production took place in the Teatro Español. During my week of theatre-going, starting Easter Sunday, I was able to see two excellent Spanish plays at the María Guerrero: Kafka enamorado by Luis Araújo (born 1956) and Transición, co-written by Alfonso Plou (born 1964); [WES 12.3, Fall 2000; 23.2, Spring 2011] and Julio Salvatierra (born 1964).

The CDN has two playhouses and rotates plays in each of them. Kafka enamorado ran 15 March to 28 April; Transición from 8 March to 7 April. With multiple playing spaces, productions limited to several weeks, and a strong emphasis on Spanish authors, Caballero has indeed offered a new opportunity to many of his fellow playwrights. Araújo affirms that this kind of welcome had never existed previously in the national theatre.

Araújo’s recent triumph at the María Guerrero was preceded in 2008 by Mercado libre (Free Market) at the Teatro Español. The playwright had sent scripts over the years to Mario Gas, a much admired Catalan director who headed the Madrid municipal theatre 2004-2012. Araújo recalls that he submitted eight to ten texts, to no avail. But Gas read Mercado libre when he served as a judge for a play contest with anonymous entries. He liked the work enough to produce it; in turn, Araújo says its success opened the doors of the Teatro Español to other contemporary Spanish authors.

A theatre critic in one newspaper affirmed that Araújo’s arrival on the CDN stage was an opportunity to celebrate a playwright who had not been performed as much as his plays merited. Indeed Araújo, like many of the playwrights of his generation, has had to struggle to reach audiences, even before the current economic crisis. A native of Madrid, he remembers a childhood in a family of modest means whose situation was complicated by his grandfather’s imprisonment after the Civil War because he had fought on the losing Republican side. Araújo’s teenage years at a Catholic seminary in Segovia introduced him to classic theatre and convinced him he did not want to enter the priesthood. He was fifteen when he returned to Madrid and sixteen when he began his university studies. At the Complutense University, he became involved in theatre groups, an activity he continued after graduation even though he needed to work to support himself. His immersion into the theatre world came with an acting role for Tábano, one of Spain’s outstanding independent theatre companies. Like many other young authors, he also wrote children’s theatre.

When he found his possibilities in Spain limited, Araújo went to France, where for a short time he was associated with the prestigious Jean Luis Barrault-Madeleine Renaud company. From France he moved to Canada, where he stayed for two years, working in Quebec theatre and teaching acting classes at the University of Montreal. He returned to Madrid in 1991, greatly enriched by his experiences abroad.

Araújo states that his exposure to another culture and to French-language theatre has been invaluable. Kafka enamorado (Kafka in Love), in my opinion, is a play that would function well for French audiences. At the María Guerrero, it was staged in the Sala de la Princesa, the playhouse’s little theatre. Because of a required duration of about an hour, it was performed in an abbreviated version of the original text. The production, directed by José Pascual, who also suggested the title that deliberately mirrors the film Shakespeare in Love, runs so smoothly that spectators would not realize there had been cuts, and the intimate space is perfect for this three-actor script. The play and the outstanding cast have been enthusiastically received by audience and critics.

Kafka enamorado was slotted in a cycle labeled from novel to theatre, but Araújo has not written a stage version of Kafka’s fiction. Rather he has sought, through letters that the author wrote from 1912 to 1917, to give expression to a romantic relationship between Franz Kafka and Felice Bauer. The focus is not political history as it was in his earlier play Vanzetti (English translation by Mary Alice Lessing), but the strategy of extensive research and use of the title character’s correspondence is similar. In both cases, Araújo read extensively in order to understand his characters’ time periods and family circumstances but always with the idea of finding the contemporary implications of history. These two plays also reveal Araújo’s interest in subjects that transcend Spain’s boundaries.

There is great temporal and spatial fluidity in Kafka enamorado. Original music, composed by Luis Delgado, underscores much of the action, following Franz’s emotions in cinematographic fashion. Pilar Velasco’s lighting likewise guides the spectator, as does the single set, designed by Alicia Blas Brunel. Consisting of slats, like decking, both for the floor and vertically on stage and extending along the side walls into the auditorium, the open slits between pieces allow spectators to see upstage action simultaneously with what is happening downstage. There are additional openings for a window and doorways. For example, stage left, we can see Felice dancing even as Franz remains center stage, reluctant to join into the engagement party merriment.

Jesús Noguero portrays the anguished Franz Kafka, who both loves Felice and fears that any romantic entanglement will detract from his writing. Beatriz Argüello doubles as Felice and her friend Grete, with whom Franz has a brief love affair before his sexual encounter with his fiancée. To make the transition from one woman to the other, Argüello moves to a doorway stage right, turns her back to the audience, and changes costumes. Chema Ruiz not only plays Max Bond, Franz’s loyal friend and editor who introduced him to Felice, but, with appropriate costume changes, also the tailor who prepares him for his engagement party, a uniformed officer in the street who threatens him, and a bellhop in a hotel in Marienbad where Franz and Felice escape together for ten days in adjoining, interconnected bedrooms. Red lighting is used to highlight that romantic interlude.

Chema Ruiz and Jesús Noguero in Kafka enamorado, María Guerrero National Theatre. Photo: Marta Vidanes.

Felice Bauer is a successful, independent businesswoman who travels a great deal. Among the commendable aspects of Rosa García Andújar’s costume design is the shift in Felice’s appearance from the conservative dark blue jacket and long skirt she wears in the opening scenes—the equivalent of a power suit from a century ago—to a feminine, summery, light gray dress she dons after the Marienbad tryst.

The failure of Franz Kafka’s romance may be attributed both to his belief that marriage would destroy his creativity and to his father’s interference in his life. Although the latter aspect is downplayed in the shortened stage version of the text, Franz’s emotional struggle is fully apparent in Pascual’s stunning production. Araújo told me that the audience when I attended on Tuesday, 2 April, was relatively cold; on other evenings, he reported that spectators had left crying. Even without tears, applause from the full house called for repeated curtain calls.

The major clue to Franz’s conflict with his father is provided in the opening scene. Downstage right, Franz, presumably locked in a bathroom, covers his face while his father yells at him to open the door and get ready to go swimming, an activity Franz truly hates. Felice will later hit a sensitive chord when she unwittingly suggests that she and Franz go for a swim.

The prime source for Araújo’s text are letters, which are read aloud to the audience. This strategy could lead to a static performance, but author and director cleverly avoid that pitfall, thus converting passive reading into dramatic action. In several scenes, Franz and Felice, separated geographically, are at opposite sides of the stage and, as writer and recipient, take turns reading fragments of letters. Lighting draws attention from one to the other. Felice is an active woman, constantly in motion, in contrast to Franz, who is or wishes to be immersed in his anguished inner world. For brief moments that inner world emerges on stage in allusions to Kafka’s fiction: when the man in uniform questions him and when he wakes up from a dream in which he has become an insect.

Temporal fluidity also leads to scenes in such varied places as train stations, hotels, homes, and a tailor shop. The lighting design reinforces shifts evoked by the actors. Changing scenes at times lead to comic moments. The most extended one is of a reluctant Franz being fitted by the tailor for the suit he will wear to the engagement party. Franz won’t hold still for measurements and even ducks out from under the tie the tailor is trying to put on him.

Not only do Argüello, Noguero, and Ruiz turn in outstanding performances, but, as revealed by photos on the CDN website, the two male actors in performance bear striking facial resemblances to the historical figures they portray (Franz and Max). The effort visually to represent accurately well-known personalities is somewhat less apparent in Transición although the king is the tallest actor in the cast and the communist leader is appropriately short and wears glasses.

The transition in question is Spain’s transformation to democracy after the long Franco dictatorship (1939-1975). The production treats, in detail, recent Spanish history, with emphasis on 1975 to 1981. Besides referring to later public events, the actors present behind-the-scenes efforts by then Prince Juan Carlos (Carlos Lorenzo) and the future president Adolfo Suárez (Antonio Valero) to liberalize Spain. Also portrayed are efforts to reach compromise with Santiago Carrillo (Eugenio Villota), leader of the Spanish Communist Party (PCE), which was outlawed during the Franco years. Because the text is so connected to the post-Franco government, Transición is the only play of the five I saw in Madrid that is local, not universal, in theme and therefore not likely to travel abroad.

The authors and directors involved in this collective project, however, were aiming for Spanish spectators who might not remember or perhaps were too young to have experienced the major changes that were guided by Adolfo Suárez, as the first democratically elected president of the new era. They believe it is essential to know about that period in order to understand the present. Key team members range in age from forty-two to forty-eight and hence had to research carefully a past they lived themselves as children and adolescents.

Transición is a joint production of the CDN in Madrid with L’Om Imprebís (Valencia), Teatro Meridional (Madrid), and Teatro del Temple (Zaragoza), a unique collaboration for Spain. The co-directors, Carlos Martín and Santiago Sánchez, are from Zaragoza and Valencia, respectively. Alfonso Plou is a founding member of Teatro del Temple in his native Zaragoza and Julio Salvatierra, the other co-author, is from Granada and a founding member of Teatro Meridional. Plou states that the idea for the project began with the three groups, who formed a working team, and was already developed when their proposal was presented to the CDN. The authors worked together half on the internet and half in person. Sixteen actors participated in preliminary workshops in Madrid; that number was reduced to the outstanding cast of eight for the final production. The cast’s fine achievement as an ensemble reveals noteworthy singing and dancing talents.

Rehearsals began in September. Prior to the March premiere at the 450-seat main stage of the María Guerrero, Transición successfully toured to various provincial cities, starting in November 2012. The text, which runs an hour and thirty minutes, without intermission, was not cut by the Centro Dramático Nacional; there were only the usual minor changes that arose in rehearsal. Like Luis Araújo, Alfonso Plou warmly praises Ernesto Caballero for inviting Spanish authors to the national theatre.

When I saw Transición, on Friday, 5 April, two days before the end of its Madrid run, the orchestra seats were all taken, as were some of the balcony ones. The audience was enthusiastic. The Spanish friend who went with me and other spectators near me smiled and laughed appreciatively not only at jokes but also at TV commercials and songs from the end of the Franco era and the movida period of new freedoms following Franco’s death. The friend, a retired teacher, believes that young Spaniards could have trouble capturing all the allusions. Spectators our evening did not appear to have that problem and critical reception, as reported in La guía del ocio, Madrid’s entertainment guide, has been very favorable. A continuing tour of the play will no doubt fulfill the goal of making Spaniards of several generations think again about the late 1970s.

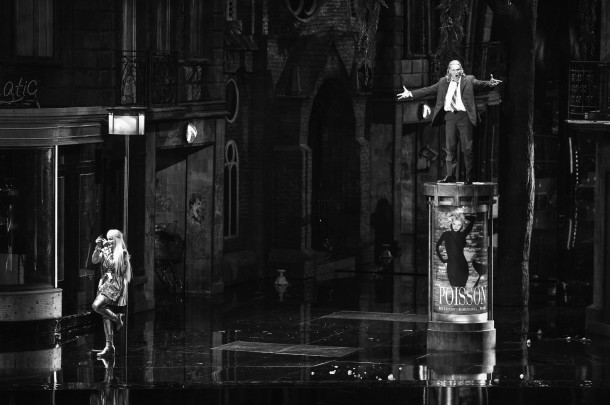

Transición is a satirical commentary on Spanish political history, perhaps inspired by works of the Catalan group Els Joglars, but on a deeper level it is also reminiscent of the psychological expressionism of Antonio Buero Vallejo (1916-2000). The central figure, Adolfo, is a patient in a mental health clinic. His memories, real or imagined, are visualized on stage. Indeed the translucent set designed by Dino Ibáñez and consisting of dozens of square panels, each divided into twenty-four smaller squares, immediately evoked for me the set of long, vertical panels divided into small squares, created by Vicente Vela for the original 1974 production of Buero’s La Fundación (The Foundation, trans. Marion P. Holt).

There are many humorous moments in the play and considerable parody of political figures except for Adolfo. Other actors change rapidly among roles; Valero is the only one in the cast (six men and two women) generally limited to a single role. Nevertheless, it is not intended for his portrayal to be historically true in absolute terms. As Jaime Salom (1925-2013); [WES 20.2, Spring 2008] pointed out to me with reference to his own history plays, theatrical truth must take precedence over historical truth.

The theatrical structure of Transición is extremely complicated. The dramatic present takes place in the early 21st century. On the one hand, a man named Adolfo, who may be suffering from Alzheimer’s, has just been admitted to a special clinic. On the other hand, there is a televised debate on the transition held thirty years after the historical events—most likely in 2001. The patient Adolfo evokes from memory that debate, along with a series of episodes beginning before Franco’s death.

Whether the memories are his is also a matter of debate; late in the play he is identified as Adolfo Martínez, a fictional usher at the congressional building who has been a great admirer of Adolfo Suárez and a witness to the unsuccessful military coup of 23 February 1981. That explanation, never fully confirmed, allows the production to deal freely with the historical Adolfo Suárez, who was admitted to a clinic in 2003 with apparent Alzheimer’s.

The set is of primary importance in this creative, entertaining, and at times beautiful production. In the opening scene, a snowy television screen appears in a panel, stage right. Adolfo watches that screen and hears voices until the screen disappears and the action shifts to a television studio. A young woman, Inés (Elvira Cuadrupani), whose knowledge of the Suárez era comes from her academic studies, is debating Adolfo himself, who disparages her information. The male moderator (Álvaro Lavin) tends to cut the young woman off, but Adolfo is clearly more frustrated than she because of what he considers misinformation being given to the Spanish public. The repeated request from the two female actors (Cuadrupani and Eva Martín), in this scene and others, that women’s issues be taken into consideration, is noticeably ignored.

Transición by Alfonso Plou and Julio Salvatierra, María Guerrero National Theatre. Photo: David Ruano.

In fragmentary fashion, the debate will continue at two other moments. Adolfo’s dreams or memories, in keeping with stream of consciousness, are not linear. All of the cast members, except Adolfo, also have functions in the TV crew. Highlights of the performance are sequences of singing and dancing that may involve all of them. The history lesson that served as initial inspiration for the production is lightened by those sequences.

Inés is a nurse in the clinic, along with other roles from Adolfo’s past. The moderator will later play Felipe González, leader of the socialist party (PSOE) who served as prime minister 1982-96, as well as Dr. González. In Adolfo’s mind, the clinic staff and other patients will be transformed into members of his family and historical figures. When Adolfo has drifted into the past or fantasy, it falls to the other actors to jar him back to present reality by identifying themselves. The shifts from patient to historical figure, aided by lighting effects, are typically done in comic tone.

In one of the funniest scenes, labeled deliria in the published text, the medieval hero El Cid (Balbino Lacosta), his daughter Elvira (Martín), and Franco’s widow Carmen Polo de Franco (Cuadrupani) inexplicably appear. Humor is foregrounded by their costumes, designed by Elena Sánchez Canales. El Cid wears an ancient helmet but has on a soccer shirt; his cape is the national flag, with a bull replacing the usual shield. Elvira’s colorful dress is made of fabric that includes flags from the contemporary autonomous regions. Carmen wears black widow’s weeds and a veil. In this wild parody, a civil guard (Lavin), weapon in hand, demands identification from these visitors from the past. A civil guard with a drawn gun is certainly a familiar stereotype, but asking the dictator’s widow for her national identity card is surprising and hence causes laughter. (Americans might compare it to asking Barack Obama for an ID so he could vote in the 2012 election.)

The delirium scene also introduces songs in the regional languages, with a translator (José Luis Esteban) aiding the civil guard in understanding the lyrics. Notable among these is the Valencian singer Raimon (Valero), whose “Al vent” (Al viento), was written in 1959 and launched in 1963 as an expression of opposition to the Franco regime. A song in the Basque language, made famous by Imanol, no doubt needs translation for many Spaniards but the Valencian lyrics are so close to Castilian Spanish that the guard’s failure to understand can also provoke laughter on a par with his failure to recognize historical and political figures.

The upper panels of the set are used for projections of actual news clips that add to historical background. The first of these is an October 1975 speech by Francisco Franco. The television moderator wants the sound deleted and says the less seen of Franco the better. That intervention also makes clear that “live television” is being faked. The “live” debate is recorded and can be revised as needed.

The last of the news clips is of Gonzalo Torrente Ballester (1910-99), a noted writer from Galicia of fiction, essays, and, in his youth, theatre criticism. Torrente’s speech should resonate in the contemporary world with Americans as well as Spaniards. He affirms that in a democracy everyone should pay his or her just taxes without deceptions.

The upper panels are also used to add beauty to the stage set. They become a starlit night near the end of the production when the patient Adolfo sits looking up at the moon. Most impressive in this respect is a final scene, when the full panels, stage right and upstage, project a lovely garden where Adolfo, emerging from his dream world, enjoys working with plants. In the touching last moments, the garden disappears, and the translucent set is bathed in blue light as the tall figure of King Juan Carlos, his back turned to the audience, aids Adolfo in walking upstage.

Of the five outstanding productions I saw during my week of theatre-going in Madrid, Transición has the largest cast. It shares with all of the other plays a relatively short duration, run without intermissions, as well as moments of humor, and, with most of them, an extended use of music and cinematographic devices.

Welcome at Commercial Stages

In the week beginning 31 March 2013, it was not difficult to find interesting plays by Spanish authors on the commercial stages of Madrid. One newspaper critic affirmed that in 2013 more of the nation’s living playwrights were being produced in Madrid than ever before, in spite of the continuing economic crisis. The three excellent productions that I saw were Hombres de 40 (Men in Their 40s), by Eduardo Galán (born 1957); [WES 18.3, Fall 2006; 19.2, Spring 2007; 23.2, Spring 2011], La visita (The Visit) by Antonio Muñoz de Mesa (born 1972), and Hermanas (Sisters) by Carol López (born 1969). All of these, like the two plays I saw at the María Guerrero National Theatre, are relatively short works, running an hour and a half or less. All address contemporary social issues, are marked by surface humor, are episodic in structure, and, to varying extents, incorporate cinematic techniques.

Galán’s play was directed by his frequent collaborator Mariano de Paco Serrano at the 500-seat Marquina. On Easter Sunday, the theatre was only half full but Hombres de 40 has been playing to larger audiences since its opening in Madrid on 14 March, after touring provincial cities starting in late November 2012. Critics have given high praise to the production and its author, some even suggesting that it is his best work to date. When it reached its fiftieth performance, Secuencia 3, Galán’s production company, announced that the run at the Marquina was being extended.

Even in the best of times, theatre is faced with financial difficulties. In Spain today those difficulties are severe. Of great concern to Secuencia 3 is the recent increase to twenty-one per cent in VAT (value-added tax) for theatre, film, and concert receipts, now categorized as entertainment, not culture. (Books and museums are still considered culture.) A corresponding increase in prices would certainly reduce ticket sales. The alternative of cutting into a theatre company’s operating budget can also have drastic results. Galán, while continuing his active involvement with the company and writing plays, has returned to his earlier profession as a teacher. When I asked him if, because of his two full-time jobs, he has given up sleep, he replied that he still manages to get five hours a night.

Uroc Teatro, with which author–director–actor Muñoz de Mesa is associated, likewise perseveres to overcome budgetary problems. It was founded in 1985 by Juan Margallo and his wife Petra Martínez. Margallo became well-known in the Spanish theatre world for his contribution to independent companies like Tábano and El Gayo Vallecano and for directing the internationally acclaimed Iberamerican Theatre Festival in Cádiz six times. As actors, the couple frequently stage works by Franca Rame and Dario Fo. Muñoz de Mesa is married to their daughter Olga Margallo. Uroc Teatro is a family enterprise that currently performs in one of the little theatres of the Teatro Arenal, in the center of Madrid, just steps away from the Puerta del Sol.

The Arenal Theatre, like the Marquina and the Príncipe, belongs to the Grupo Marquina. The consortium works together to promote productions. In the case of the Arenal, this landmark playhouse, established in 1923, has been divided into various spaces. In addition to the fifty-some-seat auditorium where Uroc rotates their plays, sometimes at two-day intervals, there is an active café-teatro that juggles thirty different performances, a company offering plays for children, and a larger theatre, where Neil Simon’s Los reyes de la risa (The Sunshine Boys) was being staged during my stay in Madrid.

The third commercial production reviewed here, Carol López’s Hermanas, is doing well. If anything it has exceeded the success of her 2005 work V.O.S. (Versió Original Subtitulada; Original Version with Subtitles). Directed by the author, Germanes opened in Barcelona in 2008, ran for more than 200 performances and, like V.O.S. before it, is being made into a movie. The play was awarded such important prizes as the Max for best text in Catalan and the Barcelona Critics’ Prize for best direction. Since 18 January, Hermanas has been playing in Madrid to near capacity audiences at the 400-seat Maravillas. Moreover, its spectators tend to be younger than those at the other plays I saw.

Eduardo Galán’s Hombres de 40 has a cast of three men and one woman. The men indeed are in their forties and are faced with personal and professional crises. Carlos (Roberto Álvarez) at forty-nine is an unemployed architect worried about mortgage payments. He has become a stay-at-home dad while his wife, Mamen, an airline pilot, flies around the world, sometimes working and sometimes playing−with another man. They keep in touch with a comic series of cell phone calls. Carlos’s younger brother Santi (Santiago Nogués), over several months of episodic action, leaves the priesthood, attempts to overcome his hypochondria, works out to become physically fit, and discovers the joys of sex. Javier (Francesc Galcerán) is a self-centered actor and producer who believes he will become rich and famous if only he can get enough money for his next project.

Despite the title, the central figure of the text is Eva (Diana Lázaro); at thirty-nine she is an unemployed biochemist, with a doctoral degree, who valiantly hopes to restore the boxing gym that was co-owned by her late father and the two brothers’ father, also deceased. She is unhappily married to Javier. There is little communication between them now that Javier no longer hears her at all. Their relationship is as distant as that of Carlos and Mamen.

As a prologue, the four characters run downstage and speak to the audience. They discuss the concept of a mid-life crisis while remembering how optimistic they had been at thirty. This introductory direct address is somewhat related to the beginning strategy of the 2011 production of Galán’s Maniobras (Maneuvers), as is the reference to art. In the earlier play about the rape of a woman soldier, Eduoard Manet’s “Luncheon on the Grass,” with its painting of a nude woman accompanied by well-clad men, is projected at the conclusion. In Hombres de 40, the action is framed by Carlos’s intermittent work and completion of a complicated jigsaw puzzle that depicts Dalí’s “The Persistence of Memory.”

In the first scene, Carlos is off to one more job interview. He calls his annoyed wife, who is several time zones away, for advice on what to wear. As he soon learns, he is not qualified for teaching positions and is overqualified to be a clerk at a department store. The solution to his economic problems, along with those of Javier, could be the sale of the gym.

A major element in the success of this production is the set, created by Verteatro, which represents an old-style boxing gym. In keeping with the boxing metaphor, scenes two through twelve are announced by a bell as if they were new rounds in a fight. According to the author, the set was inspired by the film Million Dollar Baby, and the background music, also heard between scenes, is taken from Rocky films. Another deliberate cinematic reference is the appearance of Javier, who wears glasses and a long neck scarf: any resemblance to Woody Allen is purely intentional.

Details in the set include a punching bag and two heavy bags, located to the left and between three double sets of columns that support the gym ceiling. Rear stage right is an old-style red ice chest for storing cokes.

A stunning feature of the production is the symbolic use of red for Eva’s boxing gloves and for her attractive dress in the final scene when she is headed to a breast cancer operation. There is no doubt that she is a fighter, with or without her red gloves. She enters vigorously into the struggle to keep the gym going and to beat her disease.

Earlier, when Eva returns from a doctor’s visit, clutching her medical results to her chest, Javier ignores her. As always, he is only thinking of his own project and thus learns nothing about her major health concern. The audience easily understands why Eva has separated from Javier and chooses Carlos instead to go with her to the hospital. At the beginning, the men are farcical, two-dimensional figures. Gradually Carlos and Santi evolve into more complete, realistic characters. Santi’s changes, particularly in his clothing and what he says about his new lifestyle, are on the surface and evoke laughter. Carlos’s evolution is more profound as he ceases to be Eva’s antagonist and comes to share her idealistic views on preserving their fathers’ heritage.

Despite serious themes about the economy and life-threatening illness, Hombres de 40 in general is a fast-paced comedy. When Santi makes his first visit to the gym. Eva quickly wheels out a massage table. He is exaggeratedly dismayed at needing to remove clothing. His subsequent first efforts at skipping rope are humorously clumsy, in contrast to Eva’s well-coordinated, expert display of this boxing exercise. Nogués excels as a comic actor; there is no question that his apparent clumsiness is the result of careful training. Lázaro worked out daily at a gym during the six weeks of rehearsal and has learned to genuinely enjoy boxing. In several scenes we see her punching the heavy bags. She also took classes in physical therapy in order to handle the massage scene accurately.

Hombres de 40 is likewise marked by rapid-fire dialogue in which Galán shows his mastery of traditional devices of humor. Notable among these are repetition and word play. After the second or third cell phone gag, the audience is fully prepared to laugh: if Carlos’s mentions a woman’s name, his wife invariably calls immediately. Carlos, following linguistic habits of his father, frequently stumbles on pronunciation or, like Mrs. Malaprop in Sheridan’s classic comedy The Rivals of the eighteenth century, is guilty of using the wrong word. Eva, to spectator amusement, begins to correct him automatically.

The main story line relates to the fate of the gym, left jointly to the deceased friends’ heirs. Gradually we learn that Carlos initially seeks out Eva because Javier urged him to do so: For his current theatrical venture, Javier hopes to get his hands on his wife’s inheritance to which he has no legal entitlement. When Carlos is greeted by Eva with a resounding negative to the proposal that they sell, he sends Santi to see what he can accomplish. Gradually the brothers join forces with Eva, helping her run the gym. As an architect, Carlos even drafts plans for their building’s renovation.

With the disintegration of their respective marriages, Carlos and Eva are free to pursue their romantic feelings for one another, but fate intervenes in two ways. Not only is Eva now battling cancer, but in the final scene, they receive a legal notice that the building is being claimed by the city, for half its value, under public domain. The play is open ended. The audience cannot know either what the surgeons will discover when they operate or how successfully Carlos and Eva will be able to fight city hall. Spectators will leave the theatre, however, convinced that these two, as role models for all of us, will fight.

Eva has been wearing sweats throughout the action. Her hair has been pulled back. In the final scene she is radiantly attractive with beautiful, shoulder-length hair worn down and her lovely, short-skirted red dress. Even her suitcase is red, her fighting color.

I questioned Galán about Eva’s hair. Given that the frightening lump had been discovered in the winter, had her surgery been delayed until May because the doctors had ordered chemotherapy first? In that case, wouldn’t she have lost her hair? The author replied that the theatrical company in fact had debated how the illness and cure would realistically progress and had chosen to walk a fine line with chronology. The script required enough time to elapse for the relationship between Carlos and Eva to develop and yet not enough to raise the issue of hair loss. In our discussion afterwards, the friend who went to the play with me made no mention of it, and quite possibly I was the only spectator who was attempting to analyze breast cancer treatment. Audience response to the performance was overwhelmingly enthusiastic.

La visita, directed by the author and produced by his wife, features a cast of two: the priest (Iván Villanueva), who is in charge of a Catholic school for boys and a summer camp, and a woman insurance agent (Rosa Mariscal), who for some dozen years has handled policies for the diocese. At the outset, the priest establishes his superior position by insisting that she call him “Father;” she addresses him with the formal you (usted) while he speaks to her using the informal form (tú). He repeatedly makes her bring a chair into his study when they meet to go over papers and he interrupts their conversations to water his plant.

In their episodic cat-and-mouse game, carried out over a period of weeks, the priest wants to add two new clauses to the policy: confidentiality and a definition of sexual abuse of children as a work-place accident. The action of Muñoz de Mesa’s play takes place in Spain, but the insurance clause is based on a real lawsuit from the Netherlands in which the insurance company lost its case and was required to pay the victims’ families.

Although less overtly cinematic than Hombres de 40 and Hermanas, short scenes in La visita are reminiscent of film sequences and the passage of time is indicated by visual clues. From one episode to another, the insurance agent changes jackets, ranging from bright red at first to patterned to black. That final costume points to her now being on the same level as the man in his black clerical garment.

In another visual index of passing time and shifting relationships, the priest drinks more and more wine—from a holy chalice—and munches communion wafers. After saying no to alcohol in an early scene, the agent joins the priest in drinking, from a regular glass, and even serves herself both wine in the chalice and wafers when he is not there. She also turns the tables by beginning to water the plant for the priest, and he starts to have her chair in place at his desk. Near the end of the action, she hides his chalice in a bright red waste basket.

The lights fade out between scenes as the actors visibly move the props themselves.

The see-saw action of Muñoz de Mesa’s play reveals impeccable structure built on a series of surprises. The insurance agent expresses outrage at the immoral suggestion that sexual abuse of children is a work-place accident. Later, after consulting her superiors in Barcelona, she seems to accept the proposal. When she learns that there has been a recent case of sexual abuse at the school, she is once again angered; her own son is a student there. After questioning her child, she is sure he was not victimized, but her anger returns when the priest wants to include summer camp in the policy. The recent rape, which he hopes the policy will cover retroactively, took place in the camp; her boy is planning to be with the priests during vacation.

Following each of these moments, the priest appears to be in control. But the final scene, to the audience’s delight, indicates that the woman, who is a lawyer by training, has outwitted him over and over. The agent has had him sign the confidentiality clause on-line, thus undermining his later excuse that, given his lack of computer skills, he had no idea what he was doing when he signed the second clause on-line. He never noticed an asterisk that, by scrolling down, would lead to a disqualifier. He says he can use the secretary the agent called for a clarification as a witness in his behalf, but that phone call was a fake. Through investigation the agent has discovered that this priest has a criminal record as a sex offender; therefore his signature invalidates the contract. She had brought him a check from the insurance company to settle a claim against another priest, but in the final scene, she triumphantly rips it up. The church will have to pay for the sin of sexual abuse.

The priest, in language that reminded this American spectator of Vince Lombardi, proclaims that he and the agent are engaged in a game where winning is the only thing. That game is a conflict between his greed and her sense of morality. This time, however duplicitous the agent’s strategies, morality wins out. The underlying subject is serious, but the performance, like that of Galán’s Hombres de 40, is filled with comic moments. To evoke laughter, Muñoz de Mesa uses such classic techniques as repetition and role reversals.

La visita opened at the Arenal on 2 April; I saw its second performance, the following night. The little theatre was barely half full, but spectator enthusiasm assured me that word of mouth would have a positive impact. The play subsequently was incorporated into Uroc’s spring repertory through 2 May and then was scheduled to go on tour.

Carol López’s Hermanas is an overtly cinematographic production, in part because the author–director says that she has seen far more movies than theatre. Critics have compared it to Chekhov’s Three Sisters and Woody Allen’s Hannah and Her Sisters. The comparison is more obvious with respect to Allen’s 1986 film than to the Russian play of 1901. The resemblance between publicity posters for López’s work and the movie is intentional. The play program, however, quotes Chekhov (“There’s one thing as inevitable as death: life.”) and Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina (“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”)

The circular structure of Hermanas features projections across a partial screen above the stage; these multimedia aspects were designed by Javier Franco and Diego Martín. The first projection, as a prologue, depicts the family at the tomb of the father, Ignasi, who has just died. The second projection is an epilogue that reveals the death of one of the sisters. The author comments that her two-act work follows a classic play format. Its running time of an hour and half without intermission, however, is linked to that of film.

Audience members in Spain at Hermanas will recall García Lorca’s The House of Bernarda Alba for several reasons. Guests who come to pay respects after the off-stage funeral of the father are never seen. The mother and daughters in that classic tragedy, like López’s characters, have many conflicts, and the play likewise ends with the death of one of the sisters.

On the other hand, despite the two deaths, Hermanas is a comedy. With respect to this wacky family, López has effectively put the fun back into dysfunctional, starting with preparations for the father’s funeral. The three sisters: Inés (Amparo Larrañaga), Irene (María Pujalte), and Ivonne (Marina San José) opt for a wreath of red flowers (after all, their father had communist leanings) with the phrase “Eternal love from the I’s”—if that would cost less than spelling out the names.

Both parents’ names also begin with I. The mother, Isabel (Amparo Fernández), as a widow proves even wackier than her daughters. Her favorite beverage is martinis, a choice that gives rise to some funny business. Rather than grieving, she’d like to kick up her heels. She does so in one riotous scene. She takes off her dress and, wearing a sexy black slip, dances on the dining room table. In a show with lots of singing, at times involving the whole company, her performance of a song à la Piaf, is one of the highlights. Like Transición at the María Guerrero, this production is noteworthy for its entertaining use of music and its ensemble acting.

Fernández is the only member of the cast to have performed with the original company in Barcelona, where she was awarded the Critics’ Prize for best actress.

The cast is rounded out by Irene’s teen-age son Igor (Adrián Lamana) and her current boyfriend Alex (Chisco Amado). Igor’s eagerness to lose his virginity leads to incest with his promiscuous, drug-using younger aunt, Ivonne. Although Alex’s first visit to the family on the day of the father’s funeral seems timed inappropriately, in his tolerant, good-natured way, he becomes a key support to all of them. He even seems to understand Igor−while suggesting that introducing his love partner as such to the family is not a good idea. He asks Irene to believe in his love, despite all her romantic disappointments over the years, and he encourages her photography. The epilogue projects the family album photos that she took before becoming ill.

The set design, revealing a working kitchen stage left and a dining area stage right, was created by Bibiana Puigdefabregas in Barcelona. Realistic in detail, it has an upstage stairs leading to the bedrooms and a wide doorway that provides a view of the garden, as well as additional, unseen side entrances. It might recall scenery for a traditional bourgeois play were the family members not so comically unorthodox. Except for the brief tryst of nephew and aunt, it does not follow the pattern of bedroom farce. More emphasis is given to kitchen humor. One of the repeated jokes is Inés’s obsession with making cold gazpacho and Alex’s counter effort to prepare warm broth. Accidents do occur in the kitchen and dissatisfaction with the two cooks’ culinary treats is another repeated gag.

The play completely distances itself from farce when Irene announces that she is dying. Having accepted Alex’s love, she has changed her life and her clothing. She now appears in a lovely, summery white dress with green and pink flowers. (Costumes were designed by Vicente Soler.) Isabel, in a softened tone, sits down at the table with her daughter. She tells her how very sick she had been as a child and how she, as her mother, had stayed by her side in the hospital and saved her through sheer force of will. This time her efforts fail, but the epilogue with the projection of a photo exhibit pays beautiful tribute to Irene’s life.

These three plays that I saw at commercial theatres, as well as the two I have previously noted at the national theatre, are all entertaining, thought-provoking productions that have met with audience and critical acclaim. They augur well for the future of the Madrid stage even during this period of Spain’s financial crisis.

Phyllis Zatlin is Professor Emerita of Spanish and former coordinator of translator-interpreter training at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. She served as Associate Editor of Estreno from 1992 to 2001 and as editor of the translation series ESTRENO Plays from 1998 to 2005. Her translations that have been published and/or staged include plays by J.L. Alonso de Santos, Jean-Paul Daumas, Eduardo Manet, Francisco Nieva, Itziar Pascual, Paloma Pedrero, and Jaime Salom. Her most recent book is Theatrical Translation and Film Adaptation: A Practitioner’s View. See http://www.rci.rutgers.edu/~zatlin.

-

European Stages

Since the beginning of the 1990s and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the contacts around the Baltic Sea have been rapidly increasing. Earlier some prominent Baltic theatre directors had already become well-known names in Finland and in other Nordic countries, but their visits had been occasional and cooperation had required long formal procedures. One important example of the change was the annual Baltic Circle Festival, founded in 1996 and initiated by the small Theatre Q in Helsinki, uniting the fringe theatres around the Baltic Sea. Among all these countries, Finland and Estonia belong to the same linguistic group and the renewal of Estonian independence activated theatre connections between these countries. Sofi Oksanen’s (who is both Finnish and Estonian) Purge and its realizations as play, novel, opera, and film reveal something of the range of recent collaborations between these countries.

Purge was premiered at the Finnish National Theatre in 2007. After that Oksanen rewrote the story as a novel and it was then translated into numerous languages and won several European prizes. Subsequently, the play was produced in many countries including the United States. In Estonia, it was first performed in 2010 in Tarto. The comparison between the first Finnish interpretation and the Estonian one indicates how complicated the role of theatre can be when the play takes up important current political topics.

Purge focuses on the history of Estonia, which was occupied by the Soviet Union from 1940 to 1991. The events of the play are set in two time periods—the political turmoil following the Second World War and the 1990s, when the country reestablished its independence after the disintegration of the Soviet Union. The title refers to historical events known as purges during which ideological enemies of the Soviet system were either killed immediately or deported to Siberia. Purge tells the story of an Estonian woman, Aliide Truu, who was born before the Second World War and lived through the Stalinist period until Estonia reclaimed independence. The starting point of the play is 1992, when a young woman, Zara, shows up on the yard of old Aliide’s house in the country. Her appearance brings back the memories and the shame Aliide has suppressed. Zara, who grew up in Siberia, ended up being abused, and fleeing from Tallinn, Estonia, she seeks refuge at her grandmother’s sister’s house. The flashbacks from around year 1950 show how Aliide’s family falls apart. Young Aliide, who was also raped, saved herself by sacrificing her sister and niece—Zara’s mother—during an aggressive interrogation. Aliide’s moral shame makes her fear for her family’s return from Siberia. At the end of the play, in the “present time,” Aliide helps Zara to flee. She writes a letter to her sister in Siberia and asks the family to return. Then she sets fire to the house she has lived in.

The story was not new in Estonia. Since the 1980s, the purges as historical events have been discussed widely and it has been admitted that not only the occupiers were responsible for them. Viivi Luig wrote about the topic as early as 1985 in her novel Seitsemäs rauhan kevät (The Seventh Peacetime Summer) and returns to it briefly in her Varjoteatteri (Shadow Play) (2010/2011), where she comments that “the muddy boots of the transporters have left everlasting traces onto Estonian floors.” Sofi Oksanen and Imbi Paju write in their Kaiken takana oli pelko (Behind Everything was Fear, 2009), that Estonia lost 17.5 % of its population in these purges: e.g., in 1941 about 10,000 inhabitants and in 1949 about 20,000 inhabitants were transported to Siberia. About 1,500 men were killed and 10,000 arrested of those who were hiding in the forests. Ene Mihkelson in Ruttohauta (2007) writes about “fellow travelers” who “needed to do this if they wanted to live”. He condemns those who managed to escape with their parents to the West and after 1990 came back to take back their land and houses. They blame those who had to remain, as if they had not been robbed as well. In Finland, Estonian history was generally known, but it was often hidden in order to maintain a good relationship with Russia.

The world premiere of Purge in 2007, directed by Mika Myllyaho in Helsinki, did not highlight the historical aspects of the play. The few stage objects were stylized and did not seek to remind audiences of the historical context and the political debate in Estonia. The production emphasized the humanity of the characters and the frailty of human nature. The reviews linked this production with the director’s previous work, e.g., The Lieutenant of Inishmore by Irish playwright Martin McDonagh and with a series of new plays staged in the small theatre space at the Finnish National Theatre, many of which included physical violence. The Finnish production highlighted the universal presence of violence in our world (only tangentially connecting it to the Estonian history) and the spectators did not react to the play emotionally, whereas when the Finnish National Theatre staged a visiting production in Estonia, the same performance created a strong emotional charge.

The production in Tarto, Estonia, in 2010 was directed by Liisa Smith, an Estonian director living in Great Britain. The interpretation was quite faithful to the stage directions. The performance tied the events to the Estonian locale. Estonian characters were depicted through psychological realism and deep understanding and the text was slightly adapted to add a stronger sense of relationship. The most violent scenes were related and, whenever violence was enacted on stage, the language was Russian. The performance showed who was the enemy in the historical story and gave psychological justification to the actions of the main character and especially her cathartic sacrifice in the end. The national slant was at the heart of the reception of the play, and the reviews stressed the authenticity of representation. Though different ideological and generational perspectives were reflected, the historical flashbacks touched many people on a personal level. This was a play about women, but instead of being metaphorical it reflected on the reality. In the cathartic final scene many people in the auditorium to pulled out their handkerchiefs.

The ideological slant of the Estonian production resulted from their way of reading the play. The director said that Estonians feel that the original play text offers a black-and-white representation of events, because it’s written for Finnish people. What was seen on stage is a result of the director’s research into local history: “We mustn’t deny the events of the past,” he said, and I think it’s important to remember what was done [underlining added] to the State of Estonia and Estonian people.” Estonian commentators mentioned that the playwright was a foreigner, although they acknowledged that the writer had acquired an insight into the history of the country. Less attention was focused on the fact that Oksanen’s mother was Estonian-born and that Oksanen had mentioned that the experiences of her own family had influenced the writing of the play. On the other hand, the director himself had been living abroad and had not experienced the recent Estonian re-evaluation of the past.

We can say that the play portrays events that are ideologically invested, if we agree with Jonathan Charteris-Black that ideology is “a belief system through which a particular social group creates the meanings that justify its existence to itself.” An analysis of these productions seems to indicate that Estonian society is reluctant to view its national trauma critically on stage and that theatre makers and the audience share this stance. In fact, this was the director’s choice, following a popular myth; Estonian public discussion had been more varied, as well as was the original play and especially the novel. Resorting to such a myth justifies placing yourself within the group of victims. In Estonia, the production joined a general discussion outside the theatre on the “real” history, although the performance as such had few debatable features. On the other hand, the strong focus on the actual history and on the collective memory dispelled most aesthetic discussion and the evaluation of the performance as theatre.

The world premiere of the play in Finland was less ideological, which is supported by the fact that the production was associated with theatrical tradition. As a theatrical production, it had been distanced from the reality of the spectator, which made it possible to examine the events from a distance—and perhaps it was easier to take it in as a universal depiction of personal existential contradictions—in other words, as an object of identification. Locating the play explicitly in Estonia worked better due to the general knowledge of the historical facts and the Estonian poems included in the program rather than the performance itself. The fictional characters remained, indeed, fictional—they didn’t represent the whole of any certain nation.

In these productions, the question of history is linked with the concept of genre. The printed version of Purge has been named a tragedy, but the writings on the play refer to the play as a melodrama more often than a tragedy. The play includes murder and rape, betrayal of and love for fellow humans as well as an ideological social order. Even though the play includes tragic elements, it cannot easily be interpreted as a tragedy. In melodrama, the fear of the enemy is at least as important as pity for the tragic main character. Those who are regarded as victims of injustice receive reconciliation in melodrama. In Tarto, the reviews didn’t take a position about what would have been “right” in history, but treated the events as a sort of a myth, arousing a collective emotion. One reviewer who analyzed the performance as a melodrama compared its workings with the way Hollywood films defuse social tension. The world premiere of Purge presented the play as inspiring a sense of pity for all human beings. Alienation through theatrical representation and conceptualization invites commiseration for suffering rather than condemnation of the enemy. Thus the question of collective guilt loses its weight, and the work begins to shift toward tragedy.

In fact, the interpretation of Purge in Estonia does not resemble the general recent portrayals of Estonian society. Many highly praised performances have been quite critical of this society and have employed new, often post-dramatic performance techniques. However, this indicates the difficulty of discussing nationally contested topics, and in this case removing the play from its original location allowing for more freedom in choosing one’s viewpoint. This can be seen, for example in the La MaMa production of Purge in New York in 2011, directed by Zishan Ugurlu. It stayed away from suggesting a specific national locale even though it showed the events concretely through theatrical means and directly under the eyes of the audience. There was no house in the space; the space was constructed through movement and dialogue. The director expressed her goal in these terms “I believe a woman’s body in this play is a metaphor for an occupied country which has been stuck by an asteroid, by the power of the male dominated political structures, ideology and secret violence. Under occupation, different generations of women are faced with the same challenges and they are left with impossible choices.” On stage, the dominant masculinity of the male characters erased the national features that would tone down the aggression, and the female perspective was also created in general terms. At the La MaMa Theatre, pathos was shown to the audience at a close range, but with stylized exaggeration. The story was stripped of explanations and detailed decorations, leaving only the essential on stage. The representation, however, had its shortcomings. In the context of American society, the social problems instigated by the turmoil in European countries do not carry the same meaning as in Europe, and even though the La MaMa production recognized the political metaphor, the female body in it ultimately became transparent and began to represent a “greater” metaphoric concept: turning from the incident of rape to the actions of nations and of war as a whole.

It was surprising to see how the operatic version of Purge managed to link together the national narrative and the aesthetic power of a stage production. The production at the National Opera in Helsinki in 2012 was a cooperation between the dramatist and a young Estonian composer, Jüri Reinvere, who was responsible for score, libretto and direction. He wanted to pay homage to classical opera, and he emphasized the open discussion seen in Estonia: “I claim that the past can only become the past,” he claimed, “when we have faced it eye to eye.” In the end, the pathos in opera made the tragedy more visible. The use of the chorus, for example, distanced the storyline and gave the national references wider dimensions. To a theatre researcher who is not an opera expert the music did not appear as typically operatic; instead, the challenging music for the soloists and chorus and common spectator especially was an extra distancing feature and made the message stronger: the fate appeared as unavoidable.

The Finnish film Puhdistus, directed by Antti Jokinen, also in 2012, was a Finnish-Estonian cooperation and cast with well-known Finnish actors. It did not raise any serious topical discussion, possibly because of the genre or because many others had already discussed the topics more critically and deeply. In a way Purge returned to where it began: as a representative of its art, in this case film instead of theatre.

Sofi Oksanen’s next novel was published in 2012 and will be staged as a play at the National Theatre of Finland in late 2013. It also discusses war-time Estonian history and the years after that. This time the play came after the novel, not the other way around. The new novel has not raised similar international interest to that of Purge, and Estonian history as a topic does not call for the sort of strong implicit physicality that was found in the former novel, written after the play. That physicality seems to have made Purge effective, even when the national history becomes more distant – by also making the history familiar. This situation also recalls Sofi Oksanen’s interview in the beginning, often forgotten later. She then said that she decided to write the play after having read about women during the Balkan war, and chose Estonia as topic because she knew its past and present.

Pirkko Koski, Professor emerita, was responsible for the Department of Theatre Research in the Institute of Art Research at the University of Helsinki, and was the director of the Institute of Art Research until the end of 2007. Her research concentrates on performance analysis, historiography, and Finnish theatre and its history. In addition to scholarly articles, she has published several books in these fields. She has also edited several anthologies about Finnish theatre, and volumes of scholarly articles translated into Finnish.

-

European Stages

German theatre is in a crisis which might be summed up as follows: how to remain up-to-date and “relevant” to an audience whose perceptions and attention spans have been fundamentally shaped by the speed of cyber- communication in a world of constant flux. Theatre has traditionally provided a live forum to enable us to come together to look at images of ourselves onstage, reflect on our personal, social, and political dealings with one another and, as an added bonus, gain new insights on how best to regulate our conduct to the benefit of each and all. But over the last few years in particular, our neo-liberal society has become so fragmented and individualized by the power of computerized media that it is legitimate to ask if society as we knew it in the twentieth century has practically ceased to exist. Interpersonal communication seems to take place, if at all, primarily in the form of SMSs, blogs, emails, and twitters, the only physical contact being between a person’s eyes and fingers and the computerized gadget in question.

Whether people are walking down the street or stuck in a train or bus, the majority of them–even those travelling together–seem to have their heads bowed over their smartphones and iPads, with the result that any communication with other persons in their direct vicinity is reduced to the briefest of telegrammatic snippets. On the one hand, the internet has isolated and atomized us; on the other, it has made us more globally aware. Individual knowledge once meant individual power. But now the three Big Uncertainties–climate change, terrorism (religious, urban, and nuclear), and the global economic instability resulting from the deregulation of the banking system–are ever-present in our consciousness, and all of them seem to be beyond individual control. This is further aggravated by the awareness that every cyber activity we make exposes us to global government and corporate surveillance.

In this context we are compelled to ask ourselves to what extent individual freedom still exists? And if, as Margaret Thatcher once famously claimed, society no longer exists anyway, can theatre have any social function over and beyond providing “events” and “spectacles” for individuals in a social void? Circuses indeed for those who have the “bread.” For people who have grown up in the Anglo-Saxon theatre tradition whose staple diet has been good commercial shows spiced with an occasional smattering of experiments, such questions might appear outlandish if not to say utterly irrelevant. But in Germany and the Eastern European countries, they are germane to the whole idea of what theatre should be about. In a paper published by Friedrich Schiller in the 1780s he famously asked, “What can a theatre in good standing contribute [to society]?” and suggested that it had to function as a “moralische Anstalt” (moral institution). Looking at current developments in German theatre, is this still the case?