- Account

- Commons Profile

- Activity

Andrew Lucchesi

PhD Candidate, Instructional Technology Fellow, Singer

-

Disability Writes

It’s time again for me to post my talk from the annual Conference on College Composition and Communication (#4Cs17). This time I have for you a captioned video I made using a live recording of my talk. I […]

-

CUNY-Wide Composition and Rhetoric

Andrew Lucchesi started the topic April 1 Workshop on Neurodiversity and Writing-Intensive ClassesHi everyone–

I will be leading a one-day intensive workshop for the CUNY Learning Disability project, to be held at Guttman Community College on April 1st from 10am – 1pm.

The workshop will explore how concepts of Neurodiversity and Universal Design for Learning can help instructors across the disciplines re-think their approaches to…[Read more]

-

Disability Writes

This is a draft of a lecture I will be giving at Western Washington University on February 12th, 2016. It is a work in progress, and I am open to your feedback.

Constructing Academic Disability: Student S […]

-

Andrew Lucchesi's profile was updated

-

Disability Writes

In Fall 2015, I contacted former students I had worked with during my three years teaching composition at The City College of New York. I asked them to write brief testimonials about their experiences in my […]

-

Disability Writes

My work in the classroom explicitly reflects my commitments to feminist and disability-influenced pedagogy. My classes thrive on the disability values of inter-reliance, self-determination, and respect for […]

-

Andrew Lucchesi changed their profile picture

-

-

Disability Writes

I designed this workshop for the CUNY Graduate Center’s English program orientation for new teachers, held on August 25th, 2015. It was designed to give a 50-minute introduction to the principles of Universal […]

-

Andrew Lucchesi's profile was updated

-

Disability Writes

I presented this talk on July 17, 2015 at the annual conference of Council of Writing Program Administrators in Boise, Idaho. I would be grateful for feedback, either as comments to this post, or via email at […]

-

Disability Writes

This talk was presented at the Conference on College Composition and Communication in Tampa, FL on March 19, 2015. It is part of panel E.24, titled New Directions for Disability-Studies Research: Using […]

-

Disability Writes

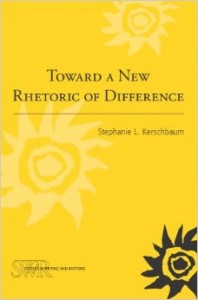

Summary and Response

Stephanie Kerschbaum’s Toward a New Rhetoric of Difference (2014) represents a turning point in disability studies research for writing studies. While the monograph–published by CCCC and […]

-

Disability Writes

This week was about trying to get back in the swing of things after my post-orals pause. The big challenge has been to get a stable writing routine going. I haven’t been completely successful. It’s difficult not […]

-

Disability Writes

So, I passed my oral exams. I did some last minute cramming, reading reviews of the books I didn’t get to and re-reading my notes on some key texts I knew my examiners liked, and ended up earning “distinction” for […]

-

Disability Writes

Andrew Lucchesi commented on the post, A year of reading, what's it good for?Thanks for the encouraging comment, Mikayla! I totally get your confusion about what I mean by “a year of reading.” Since I wrote the draft to be read to my orals committee, it assumes the reader understands in […]

-

Disability Writes

This is a draft of my 10-15 minute introduction, which I will present at the beginning of my oral exams tomorrow. Comments are welcome before 9am on Wednesday 10 September 2014.

Rather than spending this time at the beginning of my oral exam describing my three lists to you again, I thought I would talk a bit about my motivations in putting them together and how this exercise has been useful to me so far. I won’t go much in detail into what I learned from reading the individual texts (since that will certainly come up as I answer your questions); instead, I want to focus on practical concerns, on next steps based on what I know and don’t know now, on real world applications for all this thinking I’ve been doing. So, having spent a year or so reading, what’s it good for?

My motivation in putting these lists together was to help me get the scholarly acumen to pursue my personal commitments as an activist scholar. My own perspective as an activist scholar emerges from three different but related images of myself:

First, I see myself as a cultural theorist. I have a long history of work in critical race studies, feminism, and queer theory. Disability studies offered me a natural extension of my interests in social and cultural analysis, a new way of asking impertinent questions about what we think we know and how we have agreed as a society to operate.

Second, I am also a writing teacher, a worker within the contentious and pervasive institutional mechanism of literacy instruction that extends through nearly every college and university in the nation. This field offers me new ways to understand the importance of writing and education for adults, and it also gives me practical knowledge of how universities work, especially from the perspectives of writing program administrators, writing across the curriculum directors, and other hybrid faculty/administrator roles that folks like me tend to hold, often immediately after earning our degrees.

Finally, I am a person with learning disabilities who has chosen to make academic work his career. I’m someone who has difficulty carrying out the tasks of academic life for reasons believed by some to have root in my atypical brain–specifically my dyslexia. I am personally invested in understanding the kinds of challenges people like me face working in academia as it currently exists; and I am personally invested in imagining ways people like me–people we might call “neurodiverse”–can play an active role in changing the status quo of teaching, learning, and working in colleges and universities.

So, the purpose of this exam for me has not been simply to gain knowledge of a set of canonical texts for their own sake–it’s been more about utility. My aim was to get the lay of the land, as it were, for how currently published scholarship can support me in my commitments as an activist scholar.

My reading led me to some well-laid paths: for example, it led me to a robust body of scholarship by disability studies scholars in the humanities published over the last twenty-plus years. Likewise, it led me to the works of writing teachers and writing program administrators who, since the days of Open Admissions in the late 1960s, have been imagining new ways literacy instruction can support the success of students at odds with academic environments because of racial, ethnic, gender, and class differences.

It also led me to relatively obscure paths, especially in trying to better understand learning disabilities and other disabilities associated with neurological difference as they are experienced in colleges and universities. Here I had to draw upon a wide range of discourses from fields as diverse as neuroscience, psychology, educational technology, as well as the first-person accounts of memoirists and former students.

I still don’t feel I’m an expert in the topics I studied for this exam. While I have a much better lay of the land of what others have written, and while I feel I have grown much more conversant in the discourses of disability, learning, and teaching in higher ed, I still feel anxious about the gaps in my knowledge.

For instance, I still know very little about the history of disability accommodation practices on college campuses following the passage of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation act of 1973, an important landmark moment for disability in higher ed. Likewise, I don’t know, exactly, the rates at which LD or other neurodiverse student populations end up in remedial writing programs, or the ways their experiences in writing courses might contribute to the abysmal retention rates for these populations.

I don’t know these things partially because the secondary research doesn’t have much to say about them yet, or what is said is only provisional, out of date, or simply offers hints. It is partially for this reason that at the same time I’ve been doing this secondary research I have also begun my own primary research.

I have begun an IRB-approved study examining the history of disability service provision and disability policy in the CUNY system. Through a series of interviews and focus groups with current and former disability service providers, and by gathering and examining an archive of disability policy documents and service provider publications, I am attempting to study how disability politics and disability discourse have worked in real world institutions.

I am hoping that this research will move me out of the abstract realm of disability theory and into a practical understanding of how disability in higher education is affected by things like administrative policies and on-the-ground work by staff and faculty working in classrooms and boardrooms. I hope that I will discover insights from this research to help inform my work promoting access as as a progressive writing program administrator and activist scholar.

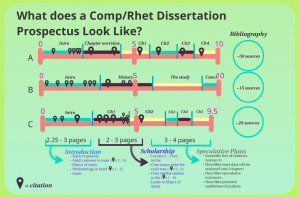

I will give just a few quick examples of the ways I’m trying to put my emerging expertise from this secondary and primary research to use. In March and July of last year, I gave presentations at national conferences arguing that writing teachers and WPAs have much to learn by better understanding the history of disability politics and inclusion on college campuses. I presented this timeline which synthesizes insights from all my research to re-present the history of progressive writing program theory, drawing new parallels to pushes for disability inclusion in higher education.

By contrasting the well-known history of writing-studies’s evolving approaches to student difference with the largely unknown history of disability activism and progressive inclusion in higher education, I hoped to help WPAs understand how current emerging interests in disability studies within composition/rhetoric represents not a disruption, but a culmination of our longstanding investments in social justice, diversity, and innovation.

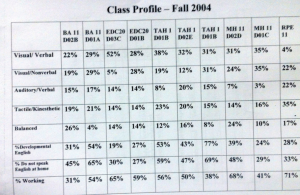

By contrasting the well-known history of writing-studies’s evolving approaches to student difference with the largely unknown history of disability activism and progressive inclusion in higher education, I hoped to help WPAs understand how current emerging interests in disability studies within composition/rhetoric represents not a disruption, but a culmination of our longstanding investments in social justice, diversity, and innovation.To those same audiences, I also presented some early findings from my interviews and archive gathering, showing how disability service provider work has direct application in the writing classroom and the work of WPAs. For instance, I described the work of Anthony Collarossi, a former disability director at Kingsborrough Community College. Collarossi–an LD specialist, a former school counselor, and a self-identified person with disabilities–developed training materials for instructors at his campus based on Multiple Intelligence theory and cognitive psychology research on different learning styles.

He also designed and piloted a set of credit-baring gateway courses for at-risk students both with and without diagnosed disabilities, courses that blended together academic support, self-advocacy, and multimodal writing instruction. Writing teachers and WPAs alike have been enthusiastic, and have easily understood the importance of recovering these kinds of disability-inspired innovations for potential application to our own practices.

He also designed and piloted a set of credit-baring gateway courses for at-risk students both with and without diagnosed disabilities, courses that blended together academic support, self-advocacy, and multimodal writing instruction. Writing teachers and WPAs alike have been enthusiastic, and have easily understood the importance of recovering these kinds of disability-inspired innovations for potential application to our own practices.Finally, I have also applied my developing expertise to my work in peer teacher training. I have given three workshops over the last year for instructors in a range of disciplines, talking about disability and universal design for learning in college classrooms. Since my responsibilities as a future WPA will certainly involve teacher training and curricular design, it’s vital for me to have good working models for helping instructors understand disability as a more than merely a medical/legal concern for service providers to deal with.

I aim to develop workshops to help instructors work through their own disability biases and come to understand the power of disability stigma, allowing them to re-envision disability not as a problem of student deficiency but as a problem of curricular access, of social discrimination, and of cultural bias. I hope the next two years of my dissertation work will give me more opportunities to develop workshop models, teacher resources, and other tools for working disability praxis in real institutional contexts.

I’ll wrap up by saying that one final outcome of this year of study, the feeling that I have found other scholars in my field interested in the intersections of disability studies and composition/rhetoric, people actively publishing and supporting the work of emerging scholars like myself. In short, that I’ve found my tribe, especially in places like the active DisabilityRhetoric online community and the faculty working in the CCCC committee on disability issues. I’ve made personal connections with scholars whose work inspires my own, and as one result of this connection, I will be presenting on a panel with Margaret Price about disability studies methodologies for composition research next March.

None of what I’ve said so far directly addresses the questions of what I’ve been reading for the last year and what I think about the ideas and concerns of individual scholars, how I make sense of the wide range of debates that focus my lists. I’m eager to talk about that now. I hope what I have done, however, is give you a sense of what I see this exercise as being good for, both so far and looking forward toward my future research and practice. So let’s get down to the questions.

-

-

-

Disability Writes

Prompt: It’s now time to confront your sources. You have already drafted through your argument in some detail, but to this point you’ve been avoiding addressing the secondary sources in detail. You have placeholders in the draft, where you know you will quote Richard Miller or discuss Margaret Price, but you have not actually settled on a quotation or written through the discussion of Price’s work.

It is very important that you do not try to rush this section of the project. And don’t expect it to be a simple or linear process.

However, working with your sources will be generative. You may have the same reaction you had last time, discover the same useful insights as before, but you may also come up with new (sometimes better) ideas on this new read through. Maybe it’s because you’ve read more on this topic now, or because you have been developing your own thoughts through writing your argument. Either way, this part of the project—wrestling the sources—will provide surprises aplenty. Embrace it.

If you set out to simply plug your sources into the outline as if they were inanimate things, they will resist. Instead, understand that wrestling the sources is meant to be a productive process, and give it the space it needs.

Process: Create a new document: begin with your works cited page from your outline draft. Put each source on its own page. Begin by choosing your favorite source (or least favorite) and start writing about it. Write about every way you remember finding the source useful to your argument. Once you get through most of these remembered insights, go back to the source itself and hunt for evidence. List key quotations under the musing. When you discover quotable material that does not connect to a remembered insights, write it separately and take some time to muse on it as well.

Depending on the number of sources you are working with, this might be a long process. I have something like fifteen sources I wanted to cite in my article; I imagine this process allowing me to move through something like three hefty sources per day, maybe five if they’re quite short and uncomplicated to work with. This means spending around a week just for writing through the sources. Don’t think you can do it in two days.

* * *

So, I missed my deadline on the CFP I was working toward (this past Friday). It just ended up taking much longer than I could manage in such a short time frame. I’m going to keep working on it, especially when my orals are done–could still find a good home somewhere. Thanks to folks who read and commented on the draft outlines.I’ve been trying to think through what went wrong with my writing on this project. Wrong isn’t quite it–what I learned by not succeeding to meet my deadline.

I faltered when it came time to work my sources into my argument. In my earlier four drafts, I had been keeping the sources at arms length, trying to figure out my own points. I had left incorporating the sources until pretty late in the process, and I got overwhelmed by the slowness and frustrations of the process: hunting down quotes, figuring out how to summarize things, making new connections. It always catches me by surprise for some reason, and it frustrates me until just give up. I stop writing.

One issue is my patchy familiarity with the texts I want to reference. I’ve read them only once or twice, and then quite quickly as part of my Orals reading lists. After multiple drafts through the argument, I end up misremembering exactly what they said—what I remember is what connection I made when reading their work, my version of their idea: this is the idea I want to use in my paper. Sometimes I can’t track down the exact moment in the text I wanted. And even when I find the moment or idea, there’s the work of explaining how the passage is useful–obvious to me, but not my readers, of course. Integrating sources means big changes and a lot of potentially chaotic revision, especially if I’m tightly tied to the argument as it sits in the last draft.

I think that’s what discourages me in my writing process. As I work through the sources, I discover things that make me feel I need to do major revision, like a whole patch of the landscape is falling into the sea. I get upset that I mis-remembered, or that I didn’t check all my sources more thoroughly before beginning the project – which would have spared me this disappointment. (This is faulty logic, of course.) I get mad it’s not easier.

I remember a particular point—I had recalled an important moment in Donna Strickland’s The Managerial Unconscious of Composition Studies in which she provided an expanded definition of the notion of curriculum, expanding it to include the administrative and technical aspects of the students’ experience. She reframed curriculum to include the whole environment of learning.

I thought this would make a useful connection to the ways that comp/rhet disability scholars like Margaret Price and Jay Dolamge (among many others) are paying critical attention to matters outside of individual classrooms (the normal sense of “curriculum”), instead critiquing things like conference accessibility, faculty bias, administrative practices.

I remember this moment so well because it provides such a clear link to disability studies and the social model of disability, which argues that disability is not caused by a person’s impairment, but rather the barriers for access present in the built and social environment. The social and cultural work of disability studies is to address the curriculum of ableism that allows for inaccessible environments, inaccessible professions, and discriminatory beliefs about disabled people.

* * *

In the future, It might be useful as I did here to to work through the sources at a bit of distance from the draft itself. When I allow myself to just muse on the sources, to be a little chaotic and dig for what the sources really mean to me, I produce some good material, including useful exposition that connects the source to my thinking. It doesn’t guarantee that what I come up with will fit the mold I had planned, but it’s something to keep me moving, at least. - Load More